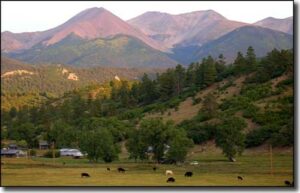

Sangre de Cristo Mountain Range

Sunset on the Sangre de Cristo’s

From Salida, Colorado, the Sangre de Cristo’s stretch 225 miles to Santa Fe, New Mexico, but if you follow their crest through all its jogs from Poncha Pass to its terminus at Glorieta Pass, the range’s length exceeds 300 miles.

- In Colorado, these are among the most dramatic peaks in the state, soaring up to 7000′ feet from the surrounding valleys with a bare minimum of foothills.

- Spanning two states, the Sangre de Cristo Mountains are one of the longest fault-block mountain ranges in the world.

Crestone Needle

In Spanish, Sangre de Cristo means “Blood of Christ”.

- The most common theory is that the name refers to the blood-red color the range assumes during sunrise and sunset.

- The Sangre de Cristo’s host 10 fourteen’ers, including the renowned Crestone Peaks, and 86 thirteen’ers, one of which is New Mexico’s state highest point, Wheeler Peak.

- You’ll find the highest point of 12 Counties in the range, as well.

- On the flanks of the Sangre de Cristo’s lies one of Colorado’s four National Parks, which protects the Great Sand Dunes, North America’s tallest dunes and a product themselves of the Sangre’s abrupt topography.

- Over a half-million acres of the Sangre’s lie within one of six federal wilderness areas.

- The Sangre de Cristo’s mark the southern end of the Rocky Mountains in Colorado, and their history since Europeans arrived is lengthier than any other range in Colorado.

- Colorado’s oldest town, San Luis, which was established in 1851, lies in the valley just west of the range.

Sunrise on the Sangre de Cristo’s

Geology

- Most people know of Denver as the Mile High City, that much of the city lies at or near an elevation of 5280 feet. However, geologists believe that Denver and its surroundings didn’t always rest at such lofty elevation.

- During the Miocene period (between 5.2 & 23.3 million years ago), the North American plate, as it drifted westward, thrust over much of the Pacific Plate.

- According to Roadside Geology of Colorado, “As the North American plate reached the Pacific mid-ocean ridge, huge new forces must have developed, forces great enough to reach the continent’s interior, lifting it up as much as 5000 feet.”

- This event not only raised Denver to its present level, it also stretched the continent to its breaking point.

- At a pair of deep faults that penetrate all the way through the crust and down to the mantle, the earth’s crust cracked, marking the genesis of the Rio Grande Rift, a massive split in the continent that reaches from the upper Arkansas River Valley all the way into Mexico.

- For reasons that are not clear, the Colorado Plateau experienced a clockwise torsion, helping to pull the rift’s edges apart and allowing the land within to drop thousands of feet.

- The land within the rift didn’t fall thousands of feet at once, but rather 5-10 feet at a time over millions of years. (A magnitude-7.3, 1983 earthquake dropped the Thousand Springs Valley west of Borah Peak, Idaho, by nine feet. This event is analogous to the numerous times that the Rio Grande Rift must have subsided.)

- The formation of the Rio Grande Rift was key in the creation of several mountain ranges.

- At the head of the Arkansas river, the Sawatch and the Mosquito ranges, formerly a single range, were severed.

- Further to the south, the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, the youngest of Colorado’s major mountain ranges, had begun to arise.

Northern end of the Sangre’s near Villa Grove

Today when you visit the Sangre de Cristo’s, the San Luis Valley is the portion of the Rio Grande Rift that you’ll see.

- This flat, expansive intermontane valley is the size of Connecticut, and while a map will tell you it’s elevation at ground level, its true base is many thousands of feet below.

- The major fault on the east side of the valley is the Sangre de Cristo fault.

- Geologists have determined that rocks found in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains are displaced by nearly four vertical miles from the same type of rocks in the valley.

- That’s right, to find the same suite of Precambrian rocks that form the core of the mountains 6-7000 feet above the valley, you’d have to dig 13,000 feet below the valley’s floor.

- Millions of years of erosion and volcanic activity have filled the valley to its present height with sediments and pyroclastic flows.

- The Sangre de Cristo’s beginnings actually predate the Rio Grande Rift, however, so we need to take a quick step back.

- During the Laramide Orogeny, the period of uplift that gave rise to most of Colorado’s mountains, the pre-Sangre’s and pre-San Luis Valley also experienced some uplift.

- This uplift was anticlinal in nature, the most common method of mountain building in Colorado. (Anticlinal: occurring at right angles to the surface.)

- The Laramide orogeny was a period of mountain building in western North America, which started in the Late Cretaceous, 70 to 80 million years ago, and ended 35 to 55 million years ago.

Sange de Cristo’s from the east side and the Wet Mountain Valley

The southern section of the Front Range (today we call the Wet Mountains) was rising concurrently and counteracted the proto-Sangre anticline on its east side, which resulted in the development of thrust faults.

- These faults allowed the earth’s crust to relieve stress as basement rock was thrust bodily over the younger sedimentary rock.

- This occurred at least eight times over, with sedimentary rock squeezed between each layer of basement rock like some octuple-decker sandwich.

- With the uplifted mountain block now in place, the stage is set for the Rio Grande Rift to shake things up.

- The creation of the Rio Grande Rift ushered in a period of earthquakes and volcanism.

- Amidst this violence, the Sangre de Christo’s continued to rise, and their uplift was enhanced by the San Luis Valley’s – and to a lesser extent the Wet Mountain Valley’s – continued subsidence along the fault zones.

Sangre de Cristo fault scarp at the northern end of the San Luis Valley.

Geologists believe that the faults along the Sangre de Christo’s are still active due to the shape of its ridges.

- Whereas the end of ridge will typically erode to a point, many of the ridges on the west side of the Sangre’s end with a triangular facet, which provides evidence of active faulting.

- Additionally, fault scarps at the northern end of the range tell us that range continues to rise at an average of an inch every one-hundred years.

- Whether this uplift is currently outpacing erosion is another question, however.

- Summing up, although an anticline provided the raw material, the range’s basement-rock core, the Sangre de Cristo Mountains stand proud as Colorado’s only fault-block range.

Northern Sangre’s in the winter

Grinding ice put the finishing geological touch on the Sangre de Cristo’s, with glaciers carving out valleys and rock faces throughout the range.

- The same prevailing winds that helped create the Great Sand, also tend to drift snow onto the eastern side of the range.

- Therefore, glaciation was less significant on the west side of the range than on the east, where glacial tongues during the height of Ice Ages reached all the way to the Wet Mountain Valley’s floor.

- On the west side, on the other hand, glaciers extended down to 9500 feet at the most, and some drainage’s remained ice-free below 11,000 feet.

- Consequently, the Sangre’s most dramatic terrain typically is found on the eastern side of the range crest, and most of the lakes are on the east side as well.

Cloudburst on Hayden Pass from the west side

History

The history of man’s interaction with the Sangre de Cristo Mountains starts thousands of years ago.

- Excavation sites in the San Luis Valley reveal that nomads hunted and foraged in the area, but there is little evidence of permanent occupation until the Capote band of the Ute Indian tribe settled there.

- The Utes are the oldest continuous residents of Colorado.

- They maintained control of the valley through the arrival of the Spanish, but in the mid-1800’s former Mexicans began to take residence in the valley, disrupting their lifestyle.

- Zebulon Pike was the first whiteman to travel through the Sangre de Cristo’s as part of his exploration of the Louisiana Purchase.

- The Pike Expedition (July 15, 1806 – July 1, 1807) was a military party sent out by President Thomas Jefferson to explore the south and west of the recent Louisiana Purchase.

- Roughly contemporaneous with the Lewis and Clark Expedition, it was led by United States Army Lieutenant Zebulon Pike, Jr.

- It was the first official American effort to explore the western Great Plains and the Rocky Mountains in present-day Colorado.

- After the U.S. took control of the region following the Mexican-American War, the government endeavored to resolve claim disputes.

- The Mexican–American War, waged between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848, helped to fulfill America’s “manifest destiny”.

- In 1851, Colorado’s oldest town, San Luis, was founded, and in 1858, the U.S. Army erected a garrison at Fort Garland in the San Luis Valley to protect settlers from the fierce Comanche tribe.

- Among his many exploits, Christopher “Kit” Carson, for whom the 14er is named, was for a time commander of this fort.

- By the 1860’s there were many homesteaders who had settled in the San Luis Valley.

Hayden Pass is one of only 2 passes thru the Sangre de Cristo wilderness

On the other side of the Sangre de Cristo Range, the Wet Mountain Valley’s recent history starts with a group of German colonists, and their influence is evidenced by several names in the area: the Colony Creeks and Lakes, Humboldt Peak, and Wulsten Baldy to name a few.

- Silver was discovered near Westcliffe, which attracted more settlers and a railroad.

- Silver Cliff was settled in the late 1870s.

- The town was incorporated in 1879 and by 1880 was Colorado’s third largest city with over 5,000 residents (behind Denver and Leadville).

Silvercliff, Colorado in the 1870’s

Maybe you’ve wondered why there are two, small, separately incorporated towns, Westcliffe and Silver Cliff, directly adjacent to each other in the mostly empty valley.

- During the silver rush, a group of Westcliffe residents felt they were being cheated by the water company.

- They packed their things, moved up the road, and founded their own town.

Sangre de Cristo’s from Howard on the East side

Since the passage of the federal Wilderness Act in 1964, the Sangre de Cristo Mountains have been repeatedly recognized for their pristine and primal qualities.

- The first wilderness designation for Colorado’s Sangre de Cristo’s had to wait another 13 years for the passage of the Colorado Wilderness Act, the flagship of which was the 226,000-acre Sangre de Cristo Wilderness.

- This wilderness area has subsequently lost acreage to the Great Sand Dunes Wilderness, which was created as part of the new Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve in 2004.

Skiing

Most of New Mexico’s ski areas are located within the Sangre de Cristo Mountains. Please visit this site for a list of New Mexico ski areas: Ski New Mexico.

In Colorado, on the other hand, Sangre de Cristo ski areas have been a losing proposition. The snowpack in Colorado’s Sangre’s simply cannot compare to the lofty totals found elsewhere in the state, contributing to the demise of the range’s two most recent ski areas.

Conquistador near Westcliffe hasn’t operated since 1992, and Cuchara Valley, in the Culebra Range, has been closed since 2000.

The Sangre de Cristo Mountains’ snowpack consolidates earlier than the other ranges in Colorado due to low snow accumulation and warmer temperatures.

Access

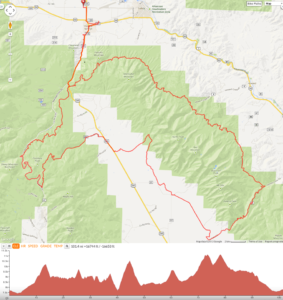

From Poncha Pass there are only two routes open to motor vehicles. Hayden Pass and Medano Pass.

- The Rainbow trail traverses the East side of the Sangre de Cristo’s from Poncha Pass to Hayden Pass. Hayden pass is very steep on the west side.

- Medano Pass from the East is steep and twisty. Once you cross over the Pass from the east there are 9 Creek crossing which then lead you into the back of the Great Sand Dunes.

- Just a few miles of very soft sand and you come to the paved road and the Sand Dunes Visitor Center.

The Rainbow trail on the Northeast side of the Sangre de Cristo’s to Hayden Pass.

Jack Walton ‘sweeping’ down Hayden Pass in 2012

See This Link for Info on the Great Sand Dunes and Medano Pass